Chapter 4

Advertising Agency Fees and Agency Value

Chapter 5

Making a Change in your Agency Remuneration Model

Chapter 6

Summary

Advertising agency fees – a comprehensive guide for marketing discusses something which, in our industry and beyond, is close to everyone’s heart.

How is a pricing structure agreed, how do agencies get paid, how should agencies get paid, and is there a better way?

For many years, TrinityP3 has worked with marketers and agencies across a variety of projects where pondering these questions and providing answers sit at the heart of challenge and opportunity.

We have built both strong experience and views over the twenty-one years of being in business, some of which are shared here.

But as much as this document talks to our approach and beliefs, it is also an exploration of what it takes to move from a static and hidebound agency remuneration model to a progressive one.

More importantly, we explore why you should be interested in making the effort – because, without doubt, a significant amount of effort is involved.

As with all papers in this series, what follows, whilst it contains insights, advice and guidance, is not designed as a pure-play ‘how to’ guide.

It’s more about defining and discussing the intricacies of the topic, and – we hope – stimulating thought, questions and discussions within your team, with your agency, and with us.

Advertising Agency Remuneration – An Overview

In the recent history of agencies, few topics have raised as much debate, disconsolation and angst as that of (depending on how you prefer to say it) agency fees, compensation or remuneration.

It wasn’t always this way. In earlier times, agencies were generally paid well, with a pricing structure calculated in simple terms against services provided, often based on healthy commission rates or a favourably structured advertising agency rate card which led to a big, guaranteed retainer. The agency fee percentage (also known as extraction, where the fee is expressed as a percentage of total client billings) tended to be higher than today.

Of course, it was a simpler time. Fewer channels of communication; less technology; fewer grey areas of skillsets between agencies and marketers; far fewer competitors; stronger personal relationships and a higher value ascribed to the skills involved in production and deployment of communication assets all gave agencies of the past a clearer run at making a good living.

The industry wasn’t without its problems, of course; but speaking in general terms, agencies did not suffer as much with inadequate remuneration, and marketers did not suffer as much with the negative consequences of poor agency performance.

Before We Go Any Further: Agency Remuneration or Agency Compensation?

In this document, when we talk about how agencies get paid, we use the terms ‘remuneration’ and ‘fees’.

However, it is worth noting that a lot of people – in fact a lot of markets, such as the US – predominantly use the term ‘compensation’.

We do not believe they are synonyms of each other, primarily because (to slip into the Queen of Great Britain’s vernacular for a minute) one is remunerated in exchange for the provision of a service or product, whereas one is compensated for something that has been lost or is deficient in some way.

So, for clarity, we use the term remuneration, but for anyone of the other persuasion, please read ‘remuneration’ or ‘fees’ as compensation, it you prefer.

Now we’ve clarified – let’s begin.

The Modern Climate of Devaluation

In today’s world, the organizational devaluation of marketing, the increased confusion around the role of marketing in an organization, an insistence on short term gain and the increasing treatment of agencies as unit-driven suppliers rather than human-IP driven partners have all significantly changed the market dynamics between agencies and the organizations they supply.

Competition is intense, and complexity is myriad. The involvement of often inexperienced procurement teams in the marketing function, alongside the proliferation of global conglomerates driving economies of scale across markets, couples with an increasing pressure on marketer’s budgets and an inability or unwillingness to change the traditional status quo or explore new ways of viewing agency value.

The net result is that over the last three decades, agency fees have steadily declined, while scope and demands increase.

Agency salaries are lower in real terms than they were 10 years ago, and teams are smaller – and less people doing more has led to recorded instances of stress and mental health issues, burnout and even, tragically, suicide.

Advertising, once a glamourous profession for young people on the first step of a career, is now famous for high stress and low entry level pay, which is an inhibitor to new talent entry.

At the other end of the scale, people in middle age and above find themselves squeezed out or labelled as unaffordable. Ageism, in this industry, is rife; but much of the issue stems from agency fees not being high enough to field senior teams on their key accounts. At the same time, advertising agency costs in other areas (such as technology infrastructure, research tools, production) have risen.

This is not to say that agencies themselves are not free from blemish, with the same global consolidation causing, at global level, greater focus on numbers and shareholder value, rather than people. It’s no surprise that the amount of small, local and independent agencies has blossomed in recent years, started by experienced people who want to return to putting people, work and true agency value first.

Some of what we’re saying here is the way of the world. But when it comes to the treatment of agency fees and agency value, there’s a lot that can be improved.

Fairness In Remuneration: A Reasonable Profit is a Reasonable Ask – and Relativity Counts!

We all believe we are fair and reasonable when it comes to agency fees. But in a conversation with a marketer for a large, global CPG company, the topic of fair and reasonable profit margins came into the discussion. TrinityP3 founder, Darren Woolley, was asked, “What is a fair and reasonable agency profit margin?” Based on the work being done with the client and the size of the account, Darren responded, “The agencies would be targeting a profit margin of 15%, or a 20% mark up on revenue”. The marketer looked shocked and replied, “That is outrageous, we made only an 8% profit margin globally last year.” Darren laughed, “I think any agency would be happy with 8% of the $640 billion you turned over last year, but not for the less than $2 million you are planning to pay them next year”.

Agencies Have Found Other Ways to Survive

In a climate of devaluation, many agencies, complicit in signing unsustainable agreements in base fee terms, or forced to meet cut-throat competitive demands in pitches, have created new ways to recoup revenue and margin that rarely benefit their ability to offer objective advice to their clients.

In more recent years, alternative revenue streams developed by agencies – media agencies in particular, but not only media agencies – have come under increased scrutiny, creating significant distrust and renewed efforts to curtail such practices.

This has been done largely without taking steps to address the fact that without these revenue streams, many agencies would go under, their base fees alone unable to sustain them. The media agency thus goes outside of a typical media agency fee structure to drive margin.

In short, the area of agency fees is, in today’s industry, profoundly unhealthy and has many knock-on effects.

We Should Play with Better Boundaries

TrinityP3’s over-arching philosophy is grounded in our 3 P’s – People, Purpose, Process.

When it comes to agency fees and agency pricing models, TrinityP3 believes that agencies should be paid fairly and commensurately, in such a way that allows a properly resourced team (People), an effective delivery of a scope of services or works (Process), and the development of a constructive professional relationship (Purpose).

TrinityP3 also believes that delivery of objective advice is a duty of care that every agency should be able to deliver without hindrance from opaque revenue streams that allow conflict of interest to flourish (Process and Purpose).

If an agency is paid fairly, it has far better ability to deliver the value required in the outputs it produces – value that should lead to commercial return for the client organization. And if digital agency fee structure, the media agency fee structure or the advertising agency fee structure is balanced, the above-mentioned objectivity is easier to achieve.

It follows that if the agency is also able to share in the success that delivery of great value and commercial returns bring (and shoulder the risk of failure) then it will act accordingly – from resourcing, to advice, to quality control, to attitude and motivation. All of which carries corresponding upside for the marketing team.

What’s Traditional in Agency Fees, and What are the Alternatives?

At this point it is worth pausing to consider some definitions.

Traditionally, agency fees are often based on ‘cost-input’ pricing models.

Progressive marketers are moving to consider two alternative pricing models – Value (Output)-Based, and Performance (Outcome)-Based.

Definitions are in the table below.

Types of Agency Pricing Models

| Pricing Model | Definition | Implication | Usage |

| Cost Input Model: Service Fee or Commission | The agency is paid either a fixed commission (calculated as a percentage extracted from the media expenditure) or fixed service fee (calculated as an incremental percentage on top of media expenditure) | The agency benefits when the budget/expenditure rises, but is left exposed when the budget reduces, or when projects are cancelled with significant works already undertaken. The reverse is true for the client, which can cause issues with alignment, trust and sustainability over time. To be sustainable, arrangements based on agency fees as a percentage of media spend generally require large and/or stable client budgets. |

The most historically embedded form of remuneration for media agencies, service fees/commissions are largely outmoded, but still exist in some places, or in distinct parts of the overall service offering (normally digitally focused – the agency, in this case, often sees the future potential given high likelihood of digital expenditure rising and is therefore happy to use this model for digital services). |

| Cost Input Model: Project | The agency is paid project to project, and submits costs for each project typically based on estimated head hours and/or production costs | The client benefits from not having to pay a retainer but project-based arrangements can be challenged by a lack of stability in personnel (no consistent team or constant account lead). Agencies do not have security but will generally offset this with increased mark-ups when compiling project costs. |

Typically found in creative/advertising and PR agencies where the scope of works is less defined, unpredictable or sporadic. Project based structures are becoming more common in creative agency fees as the taste for large retainers wains. However, advertising agency rates (in head hour terms) on project based models can be higher than a retained structure, to compensate for the lack of surety offered by a retainer. |

| Cost Input Model: Retainer | The agency is paid a fixed retainer designed to cover an estimated range and amount of different services. | The agency is paid accurately against effort (assuming that timesheet records are well kept and reconcilable against actual effort, which is a significant challenge) However, a retainer does not directly motivate the agency to prioritize effective delivery. Retainers can work well as a set and forget mechanism that provides financial stability and predictability for both parties – but a retainer can be very hard to reconcile against performance or value. There is no guard-rail against process inefficiency or general performance on either agency or client side. Furthermore. Retainers, where they are applied as a blanket single-stream model, can be inflexible. |

Typically used in agencies where a specific scope of works or a scope of services exists or is established. Retainers, while fixed, are also essentially cost-input driven. There is often no governance around required process elements or resource required for different types of output. In media agencies, retainers often represent the majority of remuneration but can be paired with variable components such as a PRIP (Performance Related Incentive Payment). In a pure cost-input structure, the agency PRIP is based on its ability to provide cheap or market-beating media inventory cost inputs (with relatively little or no regard to the commercial outcome). |

| Value (Output)-Based Model | The agency is paid a fixed fee for each defined project output, based on the value of that output. Fixed fees are defined across a range of different outputs. Each output are calibrated as appropriate (by channel, scale, type of campaign, strategic importance, origination or adaptation number of iterations, etc). and tailored to marketing needs. |

The agency is willing to accept an overall balance across multiple projects over time – some will take less time, some will take more time, but the fee remains fixed. The agency and marketer can also define which process elements and resource will be involved in different output types. By creating process frameworks within each output, the agency and the marketer are motivated to work as efficiently and effectively as possible in delivery, to improve the value of every output produced. Increases or decreases in a previously estimated annual scope, which affect the accuracy of fixed retainers, are more easily managed. |

This model is extremely rare in media agencies, where a scope of services and an estimated media expenditure, rather than a scope of works, is used to define a cost-input retainer or commission model. For advertising agencies, output based models are also relatively uncommon but are gradually finding favour in more progressive partnerships, particularly as marketers continue to move away from pure retainer-based arrangements. Often, a hybrid structure can be realized (a small retainer to cover essential day to day servicing or the percentage of time spent on the account by named individuals or positions, coupled with an output-based model to cover project scope). |

| Performance (Outcome) Based Model | The agency is paid against commercial results, typically unit sales or acquisition targets. | The agency and the client are fully aligned with the same set of commercial targets. The agency, in a pure outcome model, is remunerated only on a set dollar return against each sale or acquisition made. Agency and marketer work together on all projects with a singular aim. |

In unadulterated form, outcome-based models are extremely rare, with the exception of pure-play direct response operations in media agencies, where a bought media spot can be attributed to a call or sale via the customer quoting a code, or by monitoring of web or call centre sales uplift in the immediate aftermath of a campaign being live. It is more common to have commercial results’ as a KPI sitting within a performance measurement framework, or as part of a PRIP; typically, such incentives account for a very small minority of overall remuneration. |

The Importance of Transparency, Intent and Integrity in Making Change

Remuneration based on value or performance (rather than cost inputs) assumes a level of risk for both agency and marketer.

It requires a change not just in financial reconciliation and commercial terms, but in attitude and approach between the two parties.

It implies higher-level thinking about the purpose of the partnership, and a mutual willingness to ‘stand and fall’ on shared success and shared failure.

Ultimately, it requires a degree of integrity not always seen in marketer-agency relationships.

For any agency or marketer not prepared to take on board these requirements and implications, a move to a value or performance based pricing model may not be right.

The commitment requires both parties to be interested in fair and transparent remuneration. The marketer wishing to grind down agency fees, or the agency wishing to maximize hidden profits or benefit via inefficiency, are not right for a value or performance based approach.

We see many agencies and marketing clients fail one or more of these hurdles. In pitches or remuneration assessments, the initial talk of greater transparency, outcome-based reward, fair remuneration, succeeding and failing together often come undone in the face of reality.

The intent behind the words, for one reason or another, is not genuine. So, when push comes to shove, either client, or agency, or both, take the line of least resistance and retreat to the norm. Value or performance based pricing models either get placed in the ‘too hard’ bucket, or the can gets kicked down the road.

However, when we’ve seen it succeed, it has created longer and more fruitful marketer-agency partnerships.

So, for those of you still interested – if making the change from cost-input to value or performance based agency remuneration is difficult, then why bother?

The answer really depends on how genuine you, as an agency person or a marketing person, are about your desired achievements as a business and as a team.

Most agencies, when asked about what they want, will say that they want genuine partnership with their clients, involving a consultative approach, a seat at the top table, proper access to information and data, and a structure set up to enable their best possible work to shine, and deliver brilliant results.

Most marketers, when asked the same thing, will say that they want genuine partnership with their agencies, involving thought leadership, real challenge, innovation, objective advice, the best possible team, and a structure set up to enable their best possible work to shine, and deliver brilliant results for, and recognized by, their business.

The benefits are obvious, and the elements of repetition in the last two paragraphs is intentional. There’s no doubt that on paper, the stated aims of most sensible agencies and most engaged clients overlap with each other.

What’s not so great is that these answers are, in most cases, simply not backed up by what happens beyond a post-pitch honeymoon period.

Which is to say, the creep of supplier-style relationships with unhealthy elements of command and control style leadership, lack of clarity and flow of information in both directions, commercial terms negotiated to a point of inhibition (resourcing, ideas, effectiveness, objectivity) rather than enablement, and KPIs that strangle objectivity and drive solutions aimed at the wrong target.

The Rationale for Change

In short, where the intent is genuine and not forced or fake, the adoption of value and/or performance as the ultimate success metrics against which a partnership and remuneration model is grounded, can help to bring the standard answers about what agencies and clients want but never really achieve, far closer to reality.

Using a cost input model, how is the value of the delivered product – the value to the client, not the cost of making it – or the performance of the delivered product – the commercial return – actually calculated?

These two critical elements – value and performance – have long been used as a stick to beat both marketing teams and agencies with. Other parts of an organization will be quick to complain that the large budget line sitting against marketing is hard to justify in commercial terms. Given that a lot of marketing money can flow through agencies, it follows that in an ideal world, marketers would be able to properly track and incentivize their agencies against value, or performance, or both.

This, then, is the reason why both agencies and marketers should bother with value or performance based remuneration and move away from pure ‘cost input’ models.

A move away from cost input models provides helps to provide common purpose and unites in the same goals.

It helps to enable a two-way relationship with a far higher level of genuine objectivity. It helps to increase efficiency and effectiveness and reduce operational churn.

It motivates both parties to build, share, trust, test, evolve, learn and succeed together.

And it represents a significant part of a move to greater marketing accountability, helping to increase marketing and agency influence with the C-Suite.

Advertising Agency Fees and Agency Performance

Calibrating agency fees directly to commercial performance is something that many talk about but few achieve.

It’s not necessarily a question of possibilities. Both past and present technology has allowed performance based pricing models to exist.

Correlation between activity and sales has long been possible in direct marketing, but what about everything else?

Proliferation of communication channels has muddied the waters but advances in algorithmic modelling and data analysis mean that now, more than ever, the commercial outcomes of each part of a marketing plan, down to executional level, are attributable and quantifiable.

Opportunity, Risk, Reward.

Why, then, given the obvious opportunity, are marketers and agencies both so reluctant to move to performance based models?

From the perspective of the advertiser, the assumed risk is that the agency that performs extremely well, particularly if paid on commercial results may become a budget-breaker, with simply not enough marketing budget to pay the agency at the end of each accounting period.

From the agency’s perspective, the assumed risk is of course the opposite – failure to generate commercial results or work effectively means a loss of income or business, and additionally it is failure that the agency cannot always be held fully responsible for, given the amount of other variables in the performance mix.

For both, a structured income/expenditure arrangement, like a traditional salaried arrangement between employer and employee, is simply easier to deal with. For both, the common thread of a more entrepreneurial and speculative arrangement, is harder and becomes a question of risk management.

This leads to two questions. Why take the risk? And how?

Placing fees at risk requires willingness to focus on proportionate gain to both parties, not absolute amounts

A confectionery company was launching a new product. It had been formulated through the R&D team, but no name, packaging or advertising strategy had been developed. The agency was so excited that they proposed to do all the work at zero internal cost and only pass on the external, out of pocket-costs at net, if they could share a few cents in the dollar of revenue post break even volume. The marketing team were excited, because they had very little budget for promotion and wanted to maximize the impact. But procurement modelled the agency proposal and recommended it be rejected as if the product did exceptionally well the agency would earn a multiple of ten times on their cost, which was unacceptable. But the agency pointed out the agency would only earn this, if the client was earning fifty times as much. The proposal was rejected.

Considering a Performance Based Remuneration Model

It’s easier said than done to commit to a pure-play Performance Based model. And, it has to be said, the conditions need to be perfect for one to truly work.

100% Performance

A solar panel company sold their product online and through an inbound call center. They did their own creative in-house and their media buying agency fees were commission-based. The concern was that no matter what they spent on media, the number of sales per month remained the same. It was clear that the media agency was not optimizing the media buy based on the results and so we proposed a performance-based pricing model for the agency. Knowing how much revenue they made per month on commission and knowing the typical monthly sales, we calculated an agency fee per sale. Instead of paying commission, the agency would be remunerated against each sale delivered. There was a discount in the fee, to allow for improvement due to now optimizing the buy, and the media spend remained the same, excluding the agency commission. In the first month, with the media agency optimizing the buy daily, sales increased 250%.

However, there are numerous ways to build one, and many hybrid variants that can be explored.

What is clear, and let’s not sugar-coat this, is that Performance Based remuneration carries the highest risk, and the highest potential reward, to both agency and client. This, of course, causes challenges.

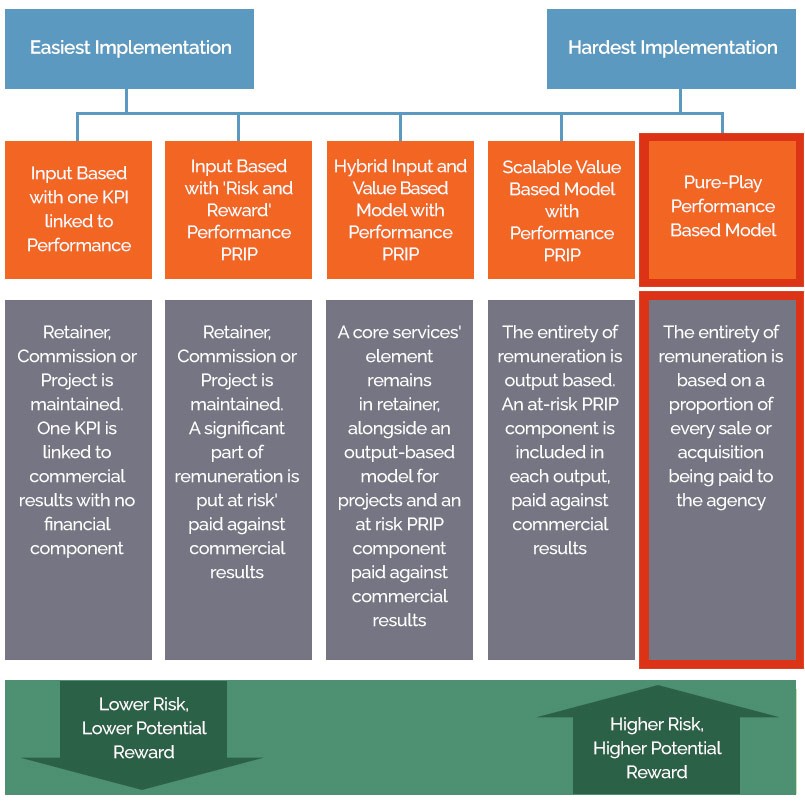

The table below shows a range of possible models that move away from a pure cost-input framework, racked against a scale of implementation, risk and reward. Highlighted in the red box is the pure-play performance-based model.

Table 2: Agency Pricing Models – Scale of Implementational Challenge

It’s important to note that the models highlighted in Table 2 are not ‘recommended’ models; nor are they exhaustive. Each advertiser and agency needs to tailor to specific requirements; moreover, there are a higher number of hybrid variants than we can usefully insert into one table.

In any event, calibration, rather than black box, is the optimal approach, one which we have applied to many clients over the years as they look to evolve their agency remuneration.

Matching fee to task

A large insurance company, managing numerous competitive brands, was looking to ‘squeeze’ their media agency retainer fee for value. (Read wanting to reduce it). Interestingly, the media agency was paid a retainer that equated to around 4% of spend. But we also noticed, that while the media spend was 40% acquisition and 60% product and brand, the agency was not incentivized on sales performance. There was a PRIP, but it was based on soft or mid-level measures such as relationship scores and media buying audit performance. Instead, we recommended making the 40% media spend on acquisition be paid 100% on results. The agency would be paid for leads and much more on conversion. The other 60% we took 10% of the fee and suggested a 30% upside for all additional audited media value negotiated at no extra cost to the client, capped at the 30% of the fee. Rather than treating agency fees as a lump sum payment, we used the fee models (Performance, Retainer and PRIP) to incentive media agency behavior that delivered measurable value to the client.

The underlying point is to highlight the sheer number of possible combinations that could be considered when tailoring to your own requirements, and the consideration that some are easier, less risky but carry a lower potential upside than others.

Change of this nature is hard. And over years of working with marketers and agencies on Performance Based models of this kind, we have experienced obstacles and concerns, worth exploring here.

Obstacle 1: Complexity and Definition.

We can encounter concerns about complexity – how, exactly, can we properly ascertain measurement and agency contribution to commercial performance?

Most businesses generally have straightforward sales or acquisition targets for each business unit; it becomes a question of aligning agency remuneration with the same targets, rather than re-inventing the wheel.

Obstacle 2: Relativity

This obstacle generally presents itself in two ways:

- The carrot (the potential reward) is too small. This often comes from the client being too reticent to accept the full consequences (risk and reward) of the structure. If the reward on offer is too small to be sustainable or meaningful, it is self-defeating for both parties.

- The objectives are disproportionate to reality. We once worked with an FMCG who proposed a sales growth bonus for the agency, where they agency could achieve a 20% lift in revenue if the company achieved their double-digit objective. The agency, correctly, pointed out that the sales objective was the same one the company had for the past 3 years and had never achieved it. It is simply not appropriate to task an agency with something that isn’t actually achievable.

Ultimately, a performance based model (or even performance related KPIs sitting as part of a traditional remuneration model) need to be properly calibrated to circumstance and reality.

Setting Sustainable Performance Targets

A CPG client had engaged TrinityP3 to assist with the negotiation and implementation of a performance incentive for their incumbent agency. The client wanted to incentivize the agency for their contribution to short term and long-term growth with metrics around brand preference and sales. The model required the agency to sacrifice 5% of the agency fee for the opportunity to ‘earn’ double the sacrifice.

The agency was happy in principle to embrace a model that used brand tracking for long term growth and sales for short term performance. The issue came to the amounts.

The client had stated the company target was to achieve 11% growth on the previous year. This had been a long-standing target and the agency asked, “When was the last time the company had achieved the target?” The answer was, “Never”. In fact, it turned out that both the metrics for sales and brand growth meant the agency would never achieve the full performance metric, and in fact, even in a good year, would be looking at never making their current fee. In the end, the project failed, because the client was unwilling to make on the performance metric and increasing the upside.

Obstacle 3: Responsibility.

An agency will often be concerned about accepting financial risk for sales results or other commercial outcomes over which it does not carry 100% responsibility. And, of course, this is valid; there are many other variables involved in making a sale, and the advertising or media cannot be held wholly responsible for success or failure.

The answer to this challenge is about mentality, measurement and balance.

To commit to a results-orientated remuneration model implies a real shift in mentality between agency and marketer – from supplier to partner.

As mentioned elsewhere in this document, the term ‘partner’ is often used with intention but not necessarily adhered to in real life.

When moving to this kind of model, a significant element of partnership becomes real. Agency and marketer are jointly invested in improving remuneration accuracy and fairness, improving process, cutting waste and refining outputs, or working towards the same per KPIs, or both.

This means that the way in which teams communicate with each other at senior level and across the day to day; the level of information shared; the access of the agency to the organization; and a shared willingness to ‘stand or fall together’ should be incorporated into working practice. This kind of approach can be defined in an engagement agreement.

From a measurement perspective – there should be an established baseline; straightforward and quantified metrics are essential; there should be an agreed performance period and payment plan; and there should be a ‘source of truth’ against which results are based, whether that be reported sales results, analytical modelling or similar.

From a balance perspective – both parties need to be comfortable with the agreement. It may be that a portion of agency remuneration is either based on, or put at risk against, commercial outcomes with the remainder is paid as a base fee.

The ideal is to ensure balance between commercial sustainability, acceptable level of risk, and ensuring that any output or outcome based component is big enough to be worthwhile.

Advertising Agency Fees and Agency Value

Earlier on, we talked about the limitations and relative inflexibility of cost-input models.

The previous chapter established that performance based models, while desirable and workable under the right circumstances, can be hard to implement and carry with them a relatively high level of risk and reward.

This thin line of tolerance means that they are not for everybody.

So, if cost input models are outmoded, and pure-play Performance Models are not for everybody, is there an acceptable alternative?

Often, when we’ve assessed a client’s needs, we will recommend a Value-Based pricing model to set the agency remuneration.

Under a cost input driven agreement, value is rarely considered, because the discussions centre on the cost of the agency services and not the relative value of the services to the client. One output, even if it has taken the agency more hours to produce, may be of less value to the client.

From the agency’s perspective, when calculating or negotiating cost-input driven fees, adding additional services justifies additional cost, as does adding more hours to a scope or project. The longer an agency spends on a project, the more it is paid – again, irrespective of end value to the client.

Of course, the client also needs to be held responsible here against the clarity and accountability of the scope of work it provides to the agency.

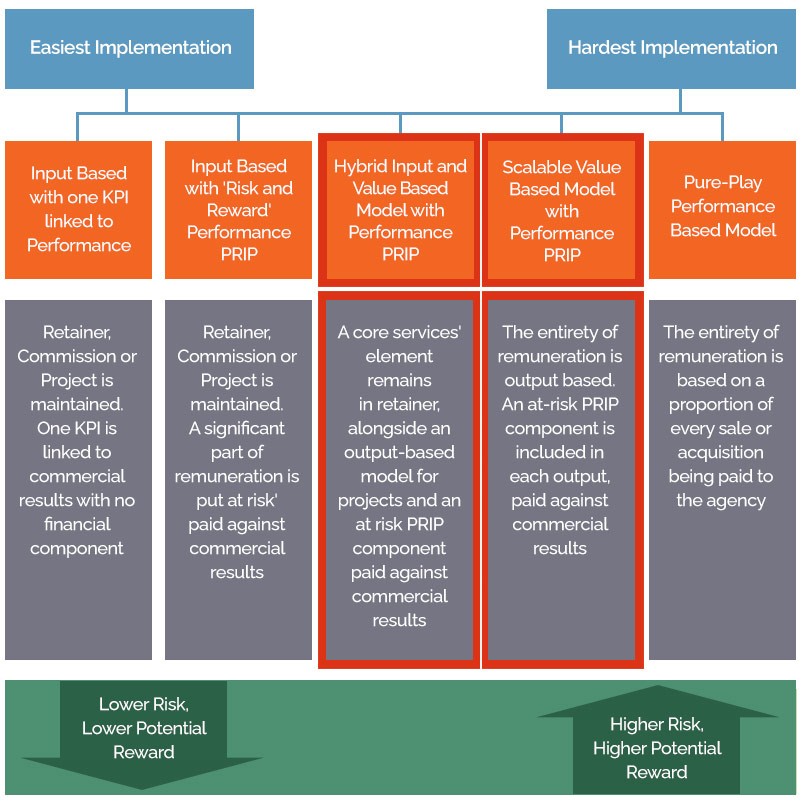

Returning to our table from the previous chapter, the value-based model options tend to be either a hybrid (essential or intangible services retained, with all project scope under a Value Based model) or a pure-play, where the entirety of remuneration is on the Value Based model. Where appropriate, performance-related KPI or incentive structures can also be built in. In the table below value-based models are highlighted in the red box.

Typically, this recommendation tends to be made for advertising agency relationships, rather than media agencies.

This is largely because advertising agencies tend to function with defined scopes of work that manifest as specific projects (with a media agency it tends to be a scope of services, which is a very different thing). However, for the right media agency relationship or set-up, a value-based structure is also possible.

Moving a media agency from commission to output based value

Over a number of years the scope of work had shifted from media related production to more direct, point of purchase and online with some or little associated media spend. The agency was complaining because under the current media commission and service fee model they were not recouping their salary and overhead costs, let alone profit.

The agency wanted to move to a retainer based on resources but because the client had a number of divisions all with their own budget, their contribution to media spend was easy to calculate but a contribution to a retainer was problematic.

Instead the client wanted to use a pricing matrix where the agency and client would agree a price or fixed fee for the services provided, therefore each division of the client would know what their contribution would be to the agency fee.

The agency argued that due to the seasonal nature of the client’s marketing activity this would mean they would not have the consistent cash flow under this model to maintain a team of resources dedicated to the client.

When the numbers were done the agency was currently under-recovering on overhead and salary by almost 20%. Under the new model the agency would improve this position to profit depending on how well they managed their resources.

So, What Exactly is a ‘Value Based Pricing Model’?

There is a good deal of confusion about what a value based model is, so let’s explained it as plainly as possible.

In simple terms, a value based model is a model where the agency is paid against the value of the output, rather than the cost of the agency input.

The client only pays for outputs of genuine value.

The value of each output is calibrated to the optimal resources required.

As a start point, historical norms are used (of course, this does take agency costs into account). But this is to establish a baseline, rather than finalize the price.

Where a value based model comes into its own is in assessment of ‘end value’ of the output to the marketer – the strategic importance, the life-stage/power or importance of the brand, the extent of usage (duration or geography) and the potential of the output to affect brand or business objectives.

So, whilst agency fees and practicalities remain factors in calculation, they are no longer the only factors, or the determining factors. This model is primarily about attributing value to each output.

The range of outputs, each with an agreed value attached, is decided based on what is going to be required in the coming period (e.g. new concept brand campaigns, adaptation work, multi or single channel, tactical retail campaigns or similar). All of which carry different levels of value. The range of outputs is worked up into a pricing matrix so that every output has a designated price, paid by the client to the agency.

New outputs can be added at any time and there is no obligation to use every output – it’s all based on actual need.

The value (price) of each output is fixed, not variable. So the agency, whether it spends 1 hour or 1,000 hours in the back end to develop an output, and whichever staff member it uses, is paid the same amount of money for that output. It becomes in the agency’s best interest to maximize its own efficiency. The standard of output, of course, remains constant, deliverable against agreed level of agency performance.

The pricing matrix can be developed for tangible and intangible outputs.

Tangible outputs are where the deliverable is defined and measurable. (Eg. Television campaign, Landing Page, Radio Commercials, Email campaigns).

Intangible outputs are those agency activities that do not have a specific measurable output (Brand strategy, Communications strategy, Channel strategy).

If intangible outputs cannot be calibrated, it is possible to run a hybrid model where these services are covered by retainer, sitting alongside the value-based pricing .

To avoid scope-creep or unreasonable demands, process guardrails are put in place and agreed.

The Benefits of a Value Based Model

From the client’s perspective, a value based model allows greater ability to measure the worth of its agency contribution, and it is an aid to efficiency of operation (just like the agency, the client cannot ‘hold up the production line’ with inefficient process).

Efficiency is gained and irritation removed by the fact that timesheets are not required to justify cost. The value is fixed and the agency manages its own time.

A value based model self-regulates by removing elements of agency service that have become ‘the norm’ but are of no real value.

Organic scope creep in a retainer model is often a culprit here. The agency, over time, takes on various tasks – competitive reviews, ad-hoc presentations or similar – which were not part of the initial agreed scope, but which have become informally built in over time, creeping into ‘scope’ under the retainer. The client is not ‘paying’ for them as such, given that they were never part of the original scoped agreement.

Where there is a complex or extensive portfolio of brands, retainers can become further muddied by the fact that different brand managers are asking the agency for different things, without reference to the overall scope, or any understanding of the value equation involved in what they’re asking for.

For example, the smallest brand asks for the same output as the largest brand because it can, and effectively pays the same amount for it, even though for the smaller brand, the work was not really valuable. In this situation the retained agency is often paid ‘too much’ because the value of many of the outputs it was producing (at the request of the clients) was simply not there, because they weren’t really needed.

The great leveller of moving to a value based model is looking at these types of outputs and asking: now that I’m actually paying for them, are they really of value?

Prioritizing based on value and necessity

A Global CPG company had a traditional agency retainer model across the region that was increasingly being questioned by management and finance. The large cost was justified by marketing based on the number of agency people retained, which had been benchmarked on cost alone. But this was a house of many brands and depending on the market, these brands varied in the value to the company, in revenue, growth of strategic competitive advantage. Yet, from the agency perspective work on the high value brand was being charged at the same rate as a low value brand.

The implementation of a value-based pricing model allowed each market to classify their brands against value and have the agency paid based on the appropriate value of the work they were doing. The development of a tiered rate card for the fees to be paid on the outputs delivered meant that the brand managers could plan their annual activity and calculate the agency fee at the start of the year to be paid monthly, like a retainer. But the high value brands would pay more for the same work as the low value brands would pay less.

The implementation of this approach delivered a 10%-15% reduction in agency fee in the first year by eliminating all of the non-essential work the agency was performing under the retainer. Work that previously the marketers had considered was free, but once it had a cost associated with it was deemed to be not required.

A value based model also allows increased budgetary foresight and surety via the fixed-cost approach, alongside improved flexibility via being able to pay the right amount for the right output, every time, even if the overall scope changes – in other words, dialing up and dialing down different outputs as necessary, based on requirements, rather than a fixed retainer which either is unsustainable to the agency if scope increases, or becomes ‘fat’ if the scope decreases.

Where the marketer is dealing with a roster of agencies with overlapping or complex and interchangeable scope requirements, a value based model can be applied across the roster. This achieves consistency, a shared sense of aim, and a greater ability to allocate work across agencies more effectively.

All for one and one for all

A financial services client had a range of non-media agencies on their roster, including a brand agency, a B2B agency, digital agency and more. The team was juggling a number of retainers and a constantly shifting scope of work across the various agency, as was the responsive nature of the marketing approach in the organization. This meant that some agencies would find themselves overworked and other underutilized. The inflexible nature of the retainer meant that moving work from one agency to another was impossible.

The marketing team decided to implement a value-based pricing model with a tiered approach aligned to brand-building, product promotion and customer acquisition or promotion. The pricing was tiered across the agencies and aligned to the pricing found in the various agencies, with a cost base that was effectively premium, median and low to the market.

With all of the agencies now working to a pricing model based on the types of outputs or deliverables, work could be managed across the roster of agencies, with the brand agency doing product and acquisition advertising on a lower agreed cost base. This allowed the marketing team to allocate work to the best agency for the job with no cost implications on the marketing budget.

In the process, a significant saving was delivered as even though the median level work for product, the until then unknown fact was that only 15% of the marketing budget was spent on brand, 30% on product and the majority was being spent on customer acquisition at a significantly lower cost base.

Finally, in attribution of value, a value-based pricing model can mesh well with a marketing team using ZBB (zero based budgeting) approach – building from the ground up, rather than assuming previous year as the base for budget calculation.

Using a value-based model naturally attributes greater value to larger or higher performing brands, with greater ability to drive commercial return. Which is exactly what ZBB is designed to do.

In fact the way in which a marketing team uses ZBB to attribute budget can be used as a guideline for determining an equivalent value equation in a value based agency pricing model, so that the two are, to all intents and purposes, consistent.

The Challenges of Establishing a Value Based Model

As with performance based models, challenges can be encountered when trying to develop a value-based pricing model.

Primarily, the measurement of ‘value’ is subjective, especially when it comes to quality control/standards; there needs to be a strong relationship, and some transparent conversations, to get to a place where values for each output type are agreed.

Even if outputs are fully defined, it can be hard to calculate cost and value, given the diversity involved in producing different outputs.

One TVC is not necessarily the same as all others; a Facebook campaign may consist of several different elements each time it is produced.

We find that calculation can be the biggest obstacle. If there is any area in which a third party expert should be brought in to advise, it is here.

Accurate calculation of individual output cost and value relies on numerous data sets:

- A balanced and representative sample of previous work costs to establish baseline cost per output. Reliance on timesheet data across too small a sample is generally not reliable enough; similarly, trying to base calculation on ‘everything’ will simply provide averages.

- Establishing a productivity baseline. If the agency is currently performing inefficiently, then calibrating output cost against historical norm will simply produce more inefficiency. Proper industry benchmarks can go a long way to reframing. However, marketing team processes, expectations also need to be accounted for and re-framed if necessary. By taking these steps when building a value-based model, both parties become more efficient and more effective. But whatever is calculated needs to be calibrated to individual circumstances.

- Ensuring that outputs are fully tailored to business needs. There is no industry ‘set menu’ here. The list of outputs should be built against precise requirements, covering all eventualities. And it can be iterated over time as new outputs become required.

- Accounting for economies of scale in overall scope. Calculation of an individual output cost is obviously affected by the amount of times that output is required over a 12 month period.

- The assessment and calibration of ‘end value’ of the output to the marketer – the importance of the work, the relative importance of the brand, and/or the potential of the work to drive business or brand objectives. The simplest way to structure this can be to create value tiers ‘high, medium, low’ or similar, and attribute a price to each tier.

It is not easy. But with the right experience, approach and data, it is achievable, and in our view, extremely worthwhile, particularly in the medium to longer term.

As mentioned above, using the marketing team’s ZBB approach as a basepoint and attempting to lever consistency between ZBB and and a value based model could be a solution.

There can also be confusion about the sheer number of outputs that need to be defined. Exploration often shows that ‘complexity’ has crept into existing operations as a result of how the marketing and agency teams have been working together, or how outputs have been defined.

Once a scope is distilled down to its essential parts, building an output based model in terms of what outputs are required, even when these appear complex, can be achieved after discovery, definition and analysis of what each output actually is.

Finally, there is the consideration of consistency, particularly in account management, or other ‘intangible’ services provided by the agency. As we’ve mentioned above, this part of an agency’s service offering can remain on a retainer so that the agency is covered for periods in between specific campaigns but where intangible services are still required.

For the other functions it is possible to specify a level of seniority is applied to certain types of tangible campaign output (for example, the involvement of the ECD in concepting a major brand launch campaign, which would naturally carry a higher value and therefore a higher cost).

But as much as the agency needs to be efficient and accurate, the client also needs to understand the full scope of what the agency is doing in producing the tangible outputs and build it in to each output accordingly – either within the output itself or separated in a retainer component. Again – transparent conversations and a degree of integrity are required to make sure of a sustainable model.

Aligning Requirements

What we have found from transitioning agency pricing models from cost based retainers to value based models is that the process is misaligned between the requirements of the marketers and the delivery by the agency. This presents itself as a very core scope of work from the advertisers and often quite a detailed and expansive delivery from the agency.

By way of example, let’s look at a brand that requires a new brand campaign and from the advertiser or brand manager’s point of view, all they require is for the agency to develop a new brand idea and execute it across three of four channels including television, digital, magazine and the like.

The other channels, such as point of sale, shopper marketing and the like, will be managed by other agencies on the roster, with executions that will be developed based on the core creative concept or ‘big idea’ to the agreed communication strategy and campaign brief.

The requirements are straightforward and understandable. The brand manager has agreed to pay the agency for participating in reviewing the brand positioning, helping in develop the communications strategy and then developing the big idea based on the communications strategy.

The agency will also be paid for then taking the big idea and developing expressions of it in the agreed media channels across television, magazine and digital display ads. But from the agency’s perspective it is not enough, because there is more to what they do than just create advertising strategy, creative concepts and production.

Making a Change in Your Agency Remuneration Model

As with so much else involved in this topic, there is no single right answer to ‘the right time’ to make what is often a fundamental change to agency remuneration.

Some circumstantial factors amongst many include the complexity of the marketer’s organization and/or marketing requirements, the tenure and style of the incumbent agency relationship, the strength of that relationship, the capacity to devote the necessary effort and time to implement, the available data-sets.

And the existing agreement needs to be respected. It’s not appropriate to force change that goes against a contractual agreement not yet expired. But this doesn’t mean a conversation can’t be initiated.

It is also vital to do the ground-work, rather than try and launch into such a big decision. It’s not a simple case of switching on a model; there needs to be proper development and consultation both internally and with the agency or agencies concerned.

Implementation Rules of Engagement

It is clear, given all the variables involved, that there is no one ‘how-to’ guide to establishing and implementing a results-orientated agency remuneration model.

However, if you plan to evolve, there are numerous considerations that can be applied to the process. For this kind of project, defining rules of engagement is always advisable.

1. Assess the current situation. Consider exactly how you’re currently operating with your agency to understand benefits, challenges and the shape of a best-fit model. Questions to consider include:

- Are the services you are paying for campaign or output based or always on?

- Are your requirements predictable or highly variable and unpredictable?

- Are the agency outputs specific and definable or undefined?

- Is your required work high volume or moderate to low volume?

- Are you managing one brand or a house of brands or products of various commercial value?

- Is the agency work seasonal or all year round?

- Does the agency make a measurable contribution to achieving either marketing or business metrics?

2. Establish clear vision and set the guard rails. Why, exactly, do you want to make a change to value or performance based remuneration? What does it solve for, what will improve, what does success look like?

Finally, and most importantly, what are the guard rails – what will you and your business realistically accept?

We will always recommend that a hard performance element is at least a part of every agency agreement – but as we’ve seen, this could encompass the entirety of how your agency is paid, or it could be one KPI sitting in an incentive structure.

If you simply want to add a performance KPI, it’s obviously far more simple to achieve, and many of the steps below may not need to be addressed.

Whatever your tolerance is, establish it before proceeding.

3. Consider the strength of your scope. Whatever model you align on needs to have an accurate scope of works or scope range at its core, enabling a workable and sustainable agreement to be structured and formed.

4. Engage your agency early. Gauging initial appetite of your agency is important. The agency must be on board early with commercial changes of this nature.

The response of your agency, and the experience it may have in developing these kinds of pricing models with other clients, may lead to insights or decisions about how to proceed with your agency (or potentially seek a market tender to find a more willing partner).

5. Open dialogue with the C-Suite, particularly sales, procurement and financial leadership. If you spend significant amounts of money with your agencies, it is vital to sell your vision internally.

Additionally, there are numerous practical considerations, one of which is often budgetary. The fear of ‘what if I don’t have enough budget to pay my successful agency’ is a real one for marketers.

An answer is to re-calibrate internal budgeting. If an agency earns a financial incentive based on sales or acquisitions, it may be appropriate to consider that funding should come from more than just the marketing budget, or that advance provision is made to ensure the reward for success is available when it becomes due.

6. Accept iteration over time. Rather than overhauling the entire structure with immediate effect, it is worth considering a staggered road-map, with stage and gate or test/learn breaks in between, so that both your team and your agency can figure out what works, and what doesn’t.

7. Ensure the metrics and measurement are robust. It has been said the best way to advance the cause of marketing at C-Suite level is to provide more robust analytics that attribute marketing effect.

If you have not invested in an analytical model, a media-mix model or similar, it is worth considering that any move towards value or performance based models should be grounded in robust and trusted metrics and measurement, and a single agreed source of truth.

8. Make it simple, balanced (level of risk and effort justified by the reward) and manageable. When moving to a value or performance based pricing model, marketer and agency both take on risk.

It is sensible to ensure that as well as being aligned, that the mechanics of the structure are not too complicated or convoluted, are fit for purpose, and that the associated reward is worth the effort.

9. Use the opportunity to reset in other areas. We have talked about the positive effects a results-orientated remuneration structure should have on an advertiser-agency relationship behaviours.

There will likely be opportunity to formally align with your agencies on making other operational or contractual changes in line with the change to remuneration structure, to improve overall outcomes.

10. Lead attitudinal and operational change. Along with your agency leadership, it is important to follow through on any changes and make them live and breathe in the attitudes and practices of your team until they are fully embedded or regarded as the norm.

When Can We Start?

Number four in our rules of engagement is ‘engage the agency early’. Early in your own process is one thing, but when is the appropriate time in context of your agency relationship?

Ultimately, a conversation can be started at any time, particularly if there is a strong and effective senior leadership relationship with the agency.

But there are relatively obvious initiation opportunities or triggers – in a pitch, at the time of contract renewal or negotiation, and as part of a performance or KPI review.

Let’s consider each of these moments.

1. In a Pitch

Pitches offer the chance to gauge the market, stress test competing agencies and is a natural break-point at which a new model could be initiated.

However, a pitch environment will not necessarily provide all the answers, certainly with regard changing an agreement with your incumbent.

A tailored set of outputs can be tabled for an agency to populate with fees, and the agencies can be required to commit up-front to commercial outcomes being a significant part of remuneration. So far, so good.

The challenge area is that with any agency other than the incumbent, a pitch will not yield the historical data of process efficiency or otherwise, existing in both teams. And the agency will not have any historical data of scope requirements; it sees only what’s in the scope put forward in the pitch and will naturally feel anxious about unknown or unaccounted variations or process kinks.

There is no real opportunity to establish or refine in discussion with a shared knowledge of the past, and what ‘needs to be fixed’. Meshing together the process is an important element in ensuring that the value of the outputs improve. Full tailoring, in a pitch environment, can be difficult.

Finally, a pitch requires an element of ‘level playing field’ assessment between agencies, meaning there is less freedom (and often time or capacity) to explore individual or different models with competing agencies.

However, this is not to say that pitches cannot at least establish a working model, on the understanding that it can be evolved over time.

This is how we often approach the establishment of a base output model in a pitch scenario – set the framework including a reasonable list of outputs, do the industry benchmarking to ensure a solid foundation and provide our client with a detailed value analysis (we can also see from this process the agencies more willing to adopt the model at all).

From here, the marketer and winning agency can use the framework and agreed output costs as a robust and workable start-point, against which refinement can occur as the relationship builds.

But overall, if the incumbency agency relationship is solid, instigating a pitch is not the best way to drive the remuneration discussion.

2. At Time of Contract Renewal or re-Negotiation

As with a pitch, contract renewal or re-negotiation of an incumbent agency agreement provides a natural watershed moment for change.

However, it is not always advisable to initiate such a big change at this time. Agencies may feel backed into a corner or surprised; and the length of time it may take to agree terms may raise legal or compliance challenges with lapsed contracts or agreements.

It is clear from previous chapters how much groundwork may need to be laid to properly execute a change to results-orientated remuneration. Therefore, it’s advisable to initiate that groundwork some time before the contract period is up, rather than at the time of renewal.

Take the time to properly envision, discuss and build a model, so that agreement can be finalized at the right time, rather than six months after the contract has expired.

3. As Part of a Performance Review

Performance reviews could represent a good moment in time to start the discussion, without hindrance of looming contractual deadlines, or the threat of pitching.

Experience suggests that agency performance reviews can suffer from dry content, lack of genuine feedback and follow-through – essentially, they’re often a tick-box item.

It’s why we created a multi-dimensional performance evaluation tool (Evalu8ing) designed to evaluate collaboration, improve alignment and drive performance across a matrix of agency-client relationships.

Including a planned first discussion about remuneration methodology at performance review time (as a broader agenda item) could be tied to shared vision and goals, areas for development or feedback in the review itself.

Remember that we’re talking here about engaging the agency early in a process, rather than presenting it with a fait accompli. When all minds are focused on performance is a good time to start.

Summary

Pitching and issues surrounding the practice of agency selection generally get a lot of attention in the trade media.

It’s hardly surprising, given the importance of new business to any agency, the general challenges and sometimes controversies involved in pitching, and the highly competitive nature of the beast.

And, of course, everyone likes to read about a juicy account win, or loss.

Nor is it for everyone. We believe that the starting intentions of both marketer and agency need to be genuine, and there’s an element of bravery involved.Proper preparation, engagement and alignment is also essential to success, as is establishment of proper metrics and measurement. This is not the kind of move that can be made overnight.

However, when properly implemented, the opportunities for improvement in many areas are great.

We hope you’ve gained insight and food for thought from our exploration of this topic. If you’d like to contact us about any of what you’ve read, please don’t hesitate to contact us here.

Agency Fee Modelling Decision Tree

What we hope this document makes clear is that there are numerous ways in which your agency can be remunerated.

We also believe that the ‘right model’ is certainly not the same for everyone. We’ve talked about principles and approaches, but we fully recognise that most, if not all client agency relationships require a degree of tailoring to fit. The bottom line is that the right fit (that is, the model that fits best with your agency, yourself and allows a strong, results-driven relationship to develop) is always the best fit.

If what we’ve said has sparked interest for you, the next step may be to answer the question – what, in reality, is actually right for my organisation and my agency?

Be it for media agency fees, creative agency fees, digital agency fees or more, the free to use TrinityP3 Agency Fee Decision Tree will help you find the right model.

Choose the right agency fee model here

Or if you have any questions or would just like a chat about your advertising agency fees feel free to contact us here and one of the team will be in touch.

About David Angell

David has more than 20 years of multinational agency and consultancy experience. An author of multiple articles blog posts and podcasts, David has worked with and advised some of the world’s best known organisations across the UK, Australasia and Asia Pacific on a variety of specialist topics including media planning and buying, agency selection, agency assessment, agency portfolio management and strategy, commercial review and marketing transformation.